by Sarah Paddick B.Arch St, B.Arch FRAIA

“brutal…”

“my first night in prison…hard concrete bed and shitty mattress…”

“noisy, hot and smelly…or freezing”

“no privacy…”

“why does it have to be so ugly?”

These are all comments from female prisoners who have lived in the mainstream block at the Adelaide Women’s Prison which is the main secure facility for women in South Australia, accommodating around 200 female offenders of all security classifications.

Figure 1. Google Earth view of Adelaide Women’s Prison, with the Mainstream Accommodation block indicated in red.

This block was built in the late 1960’s and provides around 60 beds for medium security women at the Prison. It is used as the Admissions Unit so many women will remember it as their first experience of incarceration.

As described by those who have lived there, I would agree the accommodation is terrible, and those seeing it for the first time are routinely shocked at the conditions.

The oppressive cells and narrow dark corridors leading to communal wet areas, and undersized association spaces create an utterly bleak living environment with little to redeem it. Staff interaction and supervision is difficult, temperatures are extreme, and the abundance of hard surfaces ensure it is noisy and reverberant. There is no direct access to the outdoors and the current policy of allowing smoking in the cells means it is often a smoke filled and very unpleasant environment for both staff and the women. Violent incidents are not uncommon and there is a constant simmering tension that is palpable when you enter the building.

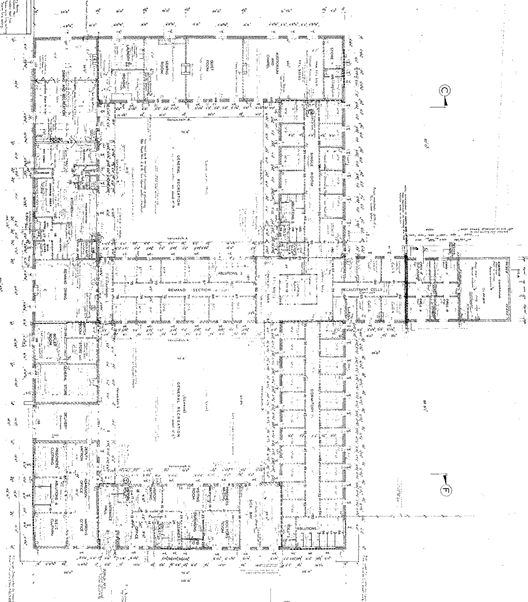

Figure 2. Original floor plan of the mainstream block.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 3. Existing courtyards are mainly used for circulation space with controlled access for prisoners.

|

Figure 4. View down corridor to cells.

|

Figure 5. Typical double cell

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 6. Shared bathroom facilities in each wing.

|

Figure 7. Shared bathroom facilities in each wing.

|

|

When finally, the decision was made to upgrade this accommodation, we were provided with an extremely limited budget, requiring us to use as much of the existing built form as possible, giving us a challenge at every step. I must admit that when we began it felt like too hard a task – to try and transform this outdated, oppressive and ugly building into something that encouraged healing and inspired hope.

Wanting to adopt a woman centred approach, our main design objectives were:

- To provide an environment that respected the privacy of the occupants,

- To provide choices wherever possible – for retreat or socialisation, temperature, food preparation, indoors or outdoors,

- To provide an attractive environment that was quiet and calm,

- To provide access to more natural light and ventilation, and direct access to outdoor areas,

- To provide a layout that addressed staff supervision, health and safety.

One of my own personal objectives was to challenge my client to reconsider the use of “standard” corrections solutions wherever I could. So often it is the case that women’s secure accommodation is just a copy of that provided for men, and does not acknowledge the different levels of risk, or the prevalence of women affected by trauma and their need for a healing therapeutic environment.

For example, we challenged our client to consider the use of carpet in the bedrooms and extensively in the association spaces. We wanted to provide a softer more residential feel, and reduce the reverberance of the spaces, but traditionally vinyl or epoxy finishes have been used for ease of cleaning and durability. By constructing a prototype bedroom early in the documentation process, we were able to convince the client to go with a carpet that was durable and easy to clean and would provide a significantly better acoustic and aesthetic outcome.

Similarly, after some robust discussion, the use of stainless steel fixtures was deemed to be excessive and the aesthetic and normalising impact of using ceramic pans and basins was seen to outweigh any perceived risk.

Our final design solution created larger bedrooms, by combining 2 cells across the central corridor, and opening out onto the dining and association spaces created by using some of the underutilised courtyard space. The additional area in the bedrooms allowed us to include a shower room, toilet room and basin area within the footprint, providing the occupants options for retreat and privacy during lockdown. The bedrooms were not designated as safe cells, but in the shower and toilet rooms we used anti ligature fittings and fixtures, considering these private spaces as posing the most risk.

Bedroom air conditioners were designed to give individual control, considering the differing needs and preferences of the cohort. The newly created association areas then addressed the remaining courtyard space which was separated from the existing circulation paths to become part of the accommodation unit, allowing direct access from the dining room via large panel lift doors.

We added colour and softness wherever possible using natural timbers, feature walls, photographic murals and pinboards. Emphasis was placed on reducing reverberance with carpeted floors and plywood acoustic panels to the ceilings. A central kitchen was provided as well as a laundry area to return some independence and control to the women. A central officer post will be completed in the stage of works currently underway, providing clear views out over both the north and south units.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 3. Existing courtyards are mainly used for circulation space with controlled access for prisoners.

|

Figure 8. New floor plan showing the northern half of the building.

|

Figure 9. New floor plan showing the southern half of the building.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 10. View across the new Association space looking down towards the kitchen.

|

Figure 11. View looking down the Association space with cell access to the right and views to the courtyard to the left.

|

Figure 12. The new dining area with panel lift doors opening out to the secure courtyard.

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 13. A new double cell. |

Figure 14. Private Shower and toilet room in the cells. |

Figure 15. The laundry area. |

The Northern Unit, Ruby, has been occupied for the last 4 months and we’ve had the opportunity to get some feedback from the women living there. Almost exclusively the comments have been positive with any negativity relating to operational issues or things out of the design teams control.

The women appreciate the beauty of the unit, and the use of colour and materials. They are proud of it and it looks as clean and new as it did the day it was handed over. The privacy that the enclosed toilet and shower provide is greatly valued, and the use of carpet and resulting softness of the spaces is appreciated.

They love being able to wash their own clothes and have that control given back to them. They make use of the temperature control in their bedrooms and made comment on the quietness of the spaces. One of the women I interviewed said, “It feels more like a ‘rehab’ centre than a prison”.

Staff have also noticed how much calmer and relaxed the women are, and how there have been virtually no incidents since Ruby has opened.

Educators have reported a greater uptake in programs and greater levels of focus and engagement when they run programs in the unit, rather than in other areas of the prison.

The women are using the larger open association spaces to do fitness activities and the raised garden beds in the courtyard are being used to grow herbs and strawberries. Fears from staff that the garden was a “waste of time” have proven to be unfounded with many of the women taking ownership and doing the maintenance.

At an early stage in the design process we also agreed that we wanted to use prisoner labour on the project, initially to reduce costs. As the design progressed and the project became more resolved in our minds, this idea to involve female prisoners became a driving force. We believed that we could create a training program that would result in actual job pathways by connecting participants to potential employers in the construction industry, by giving them experience on a “real” job site and working side by side with contractors.

We held an early registration of interest to select a managing contractor who understood our objectives and believed in the importance of what we were trying to achieve. We opened applications to all women on the site, holding job interviews to select the final team of 10. We brought local training providers on board, to provide our team a Certificate 2 in Construction as well as other construction industry training to run in parallel with the actual trade work they were doing on site.

Our final group of 10 women was made up of 3 long term sentenced prisoners and the remainder either remand or short term sentenced. They ranged in age and levels of education and experience, with some not having finished high school, and others having never had a steady job. They were all classified as low risk by Corrections, and all lived in the residential low security accommodation at the bottom of the site.

The women start work at 7am and spend a full day on site. Some of the week is spent doing the education component, but most of time they are working on the build. They were involved in all aspects– demolition, concrete, carpentry, steelwork, brickwork, first and second fix services, linings, tiling, painting, joinery and landscaping. They are responsible for keeping site clean and the site sheds maintained, and some are assisting with aspects of site administration.

Each day they are assigned to a subcontractor who is required to provide a training component in addition to their scope of works. This has seen some of the team excel in particular trades, whilst others have been happy to be support labourers. The intention was that the women would get a taste of a variety of tasks and ultimately find one that they might see themselves having a career in.

Over the first few months the women all reported that they had lost weight, they were sleeping better and were loving coming to work each day.

The subcontractors also told us that they were impressed by how hard the women worked and, in some instances, they expressed an interest in hiring them post release.

More importantly though we saw changes to the women’s confidence and self-esteem. One woman who had a difficult history of domestic and sexual abuse initially expressed her fear at having to work so closely with men. Over time, as she began to interact with the subcontractors and understand that she was always going to be treated with respect, she began to gain confidence and loose her fear.

The contractors themselves were challenged to cast away their preconceived ideas of who or what an offender is, and better understand the human face of incarceration. The social aspect of the building site was encouraged, with contractors and the women taking ‘smoko’ together and having regular Friday BBQ’s.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 16. A collection of shots of our construction work team on site. |

The project has now been running for 18 months and six of our original work team have either transitioned into the Pre-Release Centre or completed their sentence and left the prison. The four who have left are now all working in the construction industry in jobs our team have found for them. We have set up some pathways with several employers and are now also trying to find opportunities to get some of the more skilled women into apprenticeships. Demolition, site labouring and traffic management have proven to be good “first steps” but we believe that some of the women who are coming through this program can potentially achieve much more. Having said that the hurdles that face ex-offenders cannot be underestimated – lack of a driver’s licence, police records and clearances, as well as community perceptions – and I find we are constantly having hurdles placed in front of us.

We now have a second group of 10 women enrolled in the program, ready to start work and training on the second half of the upgrade, and the plan is that the 4 more experienced women from the first team will be employed on another major redevelopment project happening at the prison. From the Managing Contractors perspective, they will be classed as 2 first year apprentices, 1 site labourer and 1 site administration support person.

We’ve branded the program as the UTurn Construction Pathways program and hope to see it continue and develop. It’s shown how a social justice initiative can develop with the input of different people across different industries. In this case, the South Australian Department for Correctional Services, Totalspace Design, TAFE (Training providers) and Mossop Construction + Interiors, plus all our pathway employers, have collaborated and worked together to create what we hope will be an ongoing program that will see its participants find long term careers in the construction industry, or at the very least improve their confidence and self-esteem.

If you would like to track the progress of the project you can connect with Sarah Paddick on Linkedin, or like the Totalspace Design Facebook page, or follow our Instagram account.