One of the simplest learning environments is the playground. It is also one of the most important. Yet often its importance to children’s development, as well as the design opportunities it presents, is overlooked by architects.

Susan Solomon's new book, The Science of Play: How to Build Playgrounds that Enhance Children’s Development, takes a fresh approach to the subject of playgrounds. This important overview explores the importance of play and playgrounds for children, with special focus on play solutions that encourage risk taking, succeeding and failing, planning ahead, experiencing nature, and making friends. It is also a remarkable book because it asks us to aggressively rethink playgrounds and the need for play, despite our over-litigious society's drive to eliminate risk from life. In doing this, she stresses that parents need to recognize that some level of risk is desirable and even necessary to children's development. She is also asking us, as parents, public officials, design professionals, and those responsible for children's lives, to take risks ourselves: In short, to be more inspired and creative ourselves in the interest of childhood betterment.

Many, if not most of our playgrounds and play equipment, Solomon notes, have become boring: uniform, unimaginative, banal. They do not encourage play; they are not stimulating places where kids want to be; nor do they enliven their communities.

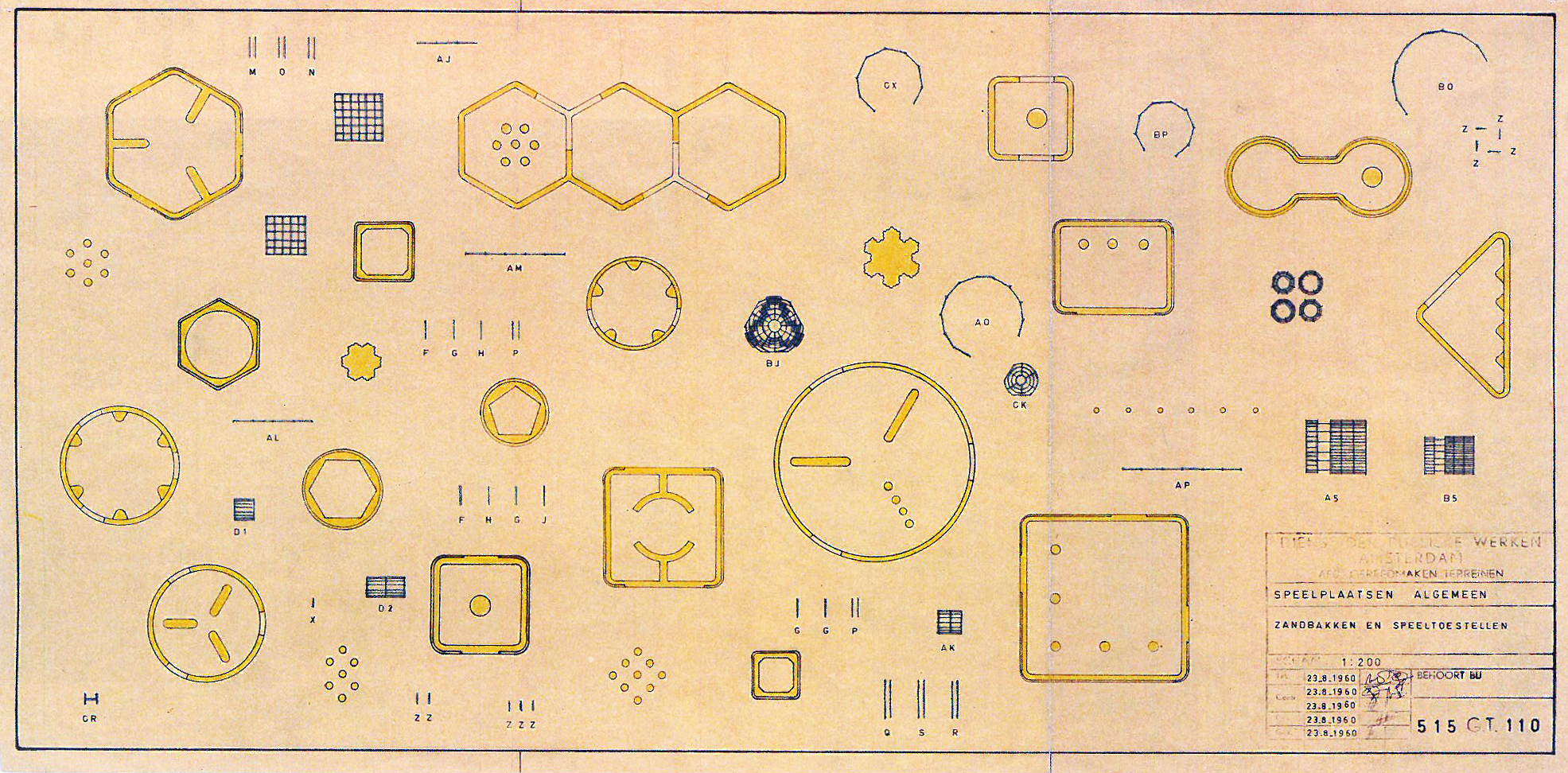

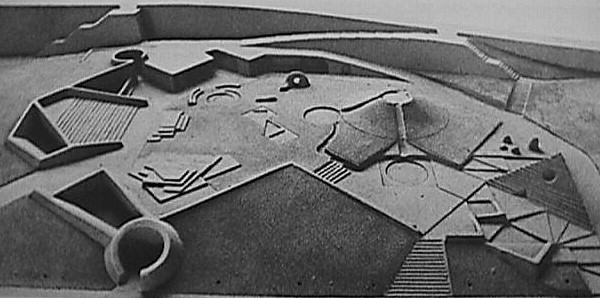

Citing behavioral science studies, Solomon stresses the developmental importance of energetic and inspired play. The book is a call to action for re-introducing such stimulating play. She includes more than 50 best practice state-of-the-art yet affordable examples from around the world, with special focus on foreign solutions in England, Europe and Japan that "avoid the rigidity and predictability of traditional playground equipment" to create inspiring, stimulating environments for children. These examples are all tastefully selected, with special emphasis on sustainability, and range from such diverse projects as the intimate Norwegian fire pit and Cave by Haugen/Zohar Arkitekter to the large knitted fabric climbing sculpture in Japan by the artist Toshiko Horiuchi MacAdam. She also includes U.S. examples by architects such as the Rockwell Group; landscape architects such as Michael Van Valkenburgh, and Steven Koch; as well as by artists, that manage to enrich play while still meeting safety guidelines. She positions these in a historical context which includes the pioneering playgrounds of Aldo van Eyck, Louis Kahn and Isamu Noguchi. She writes also how playgrounds can become multi-use vibrant community hubs.

As a practicing design professional, I admit guilt to selecting dumbed-down yet "safe" playground equipment, as a safeguard against potential litigation. And yet one of my favorite playground experiences was at a rustic in Finland, where my young son could do things that would never have been possible at a public park in the US. There he was able to use a long rope swing to land on old tire floating in the middle of a lake. In simulated rapids, while struggling to retain my grip on him while I watched kids shoot past us in the swift water to wind up who knows where, it occurred to me that not only did these Finns seem hardier, heartier, and less litigious than we Americans, but it also seemed their kids were having far more fun.

Finland has received the attention of educators and policymakers worldwide because of its impressive performance on international benchmarking tests. And Finnish educators, it is found, knowingly incorporate play into their education curriculum. The principal of Kallahti Comprehensive School, Finland, said, “The children can’t learn if they don’t play. The children must play.”

“Teachers in Finland spend fewer hours at school each day and spend less time in classrooms than American teachers,” writes Lynn Hancock in Smithsonian Magazine. “Teachers use the extra time to build curriculums and assess their students. Children spend far more time playing outside, even in the depths of winter. Homework is minimal. Compulsory schooling does not begin until age 7.” Hancock quotes Kari Louhivuori, a teacher and principal of Kirkkojarvi Comprehensive School in Espoo, “We have no hurry. Children learn better when they are ready. Why stress them out?” And Finnish teacher Maija Rintola adds, “Play is important at this age. We value play.”

Playgrounds have more often been the focus of landscape architects such as Michael Van Valkenburgh, who have creatively incorporated inspiring play experience into their public and municipal projects. Increasingly, architects are turning attention to playgrounds as a design problem. David Rockwell, together with his architecture and design firm The Rockwell Group has developed their “Imagination Playground.” After studying playgrounds for more than five years, the Rockwell Group says, they identified the need for more open ended play activities that help promote a child’s natural creativity. Their design solution, “Imagination Playground,” is a set of large blue foam components that allows children to design and build their own “portable playground.” “The large size of the blocks increases social interaction and collaboration,” Rockwell says, “as children work together to move them and construct temporary worlds and create their own games.” Imagination Playground focuses on “encouraging child-directed, unstructured free play. "With a focus on loose parts," the playground's website explains, "it offers a changing array of elements that allows children to constantly reconfigure their environment and to design their own course of play."

Susan Solomon’s The Science of Play focuses attention on the little explored yet tremendously important and influential environments of children's playgrounds, and through many specific examples shows how they can be repositioned from the stultifying settings they too often are to the inspiring, stimulating and educational settings they need to be. It’s an especially important reminder for architects, who often control much of this crucial environment of children’s formative years.

John W. Clark, AIA Co-Chair,

Subcommittee for Alternative Learning Environments

November 2016